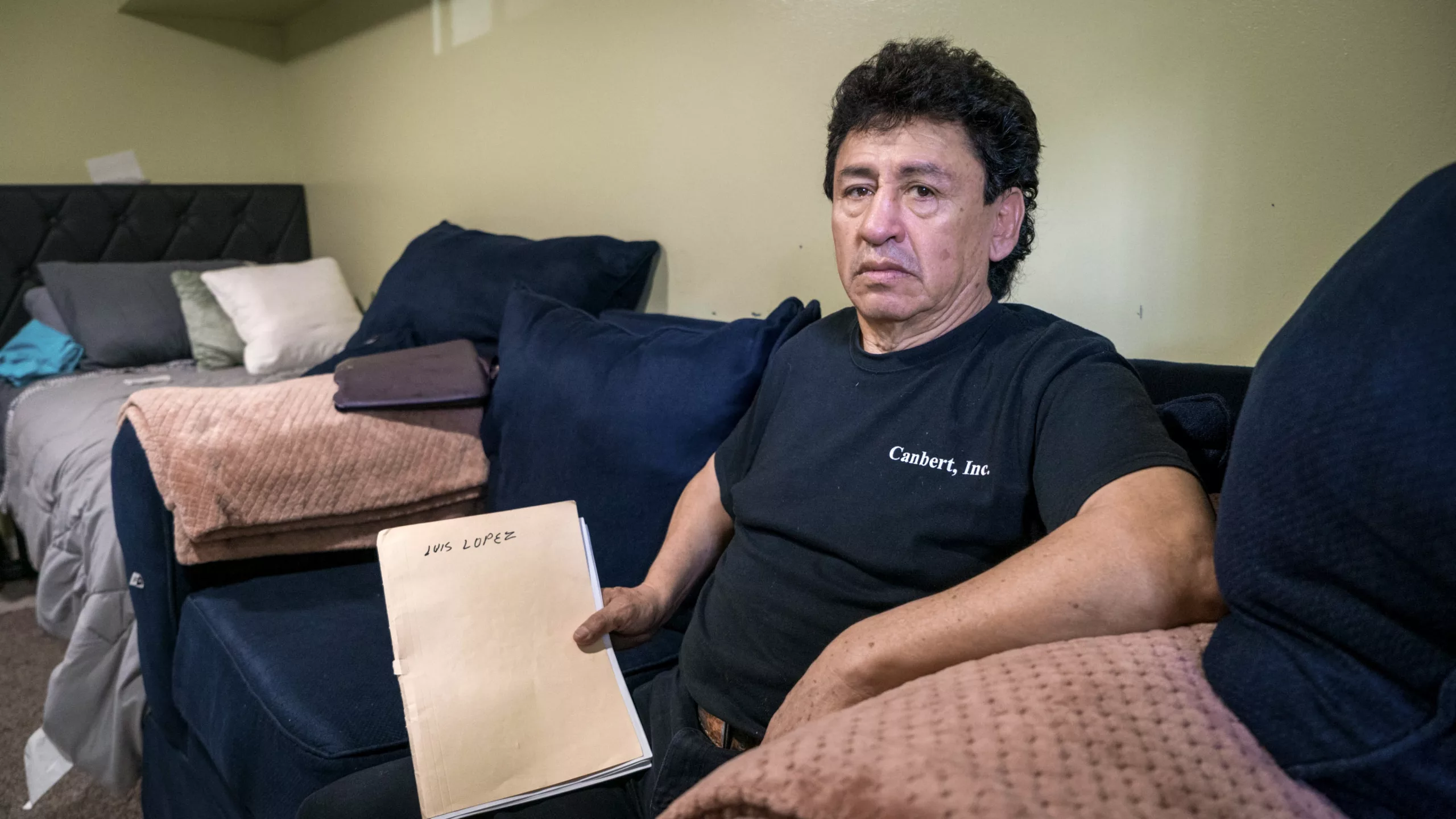

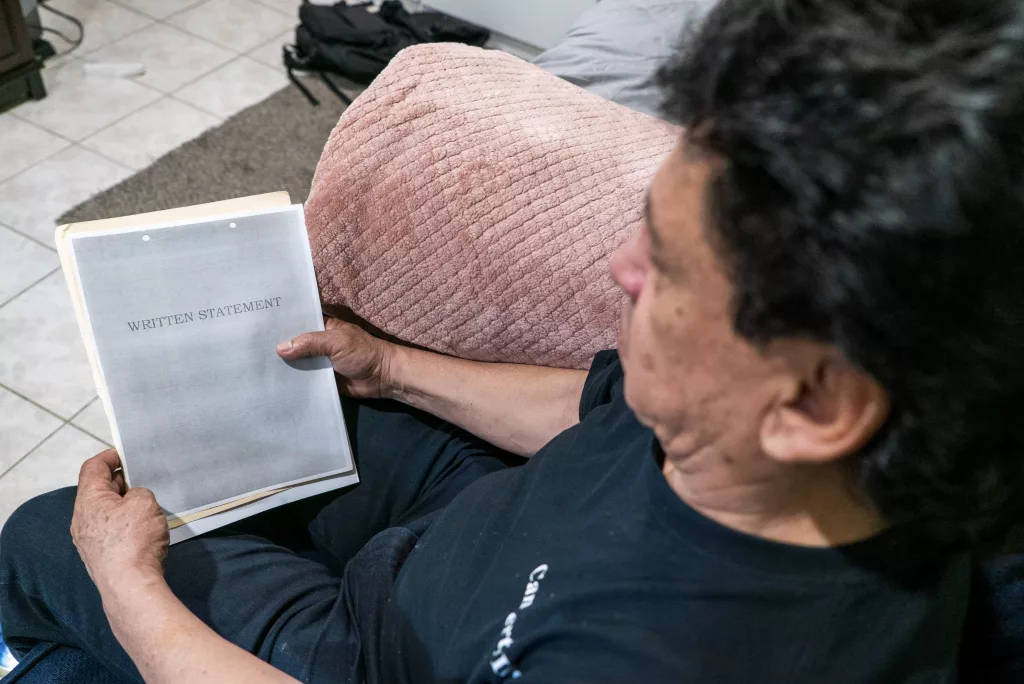

On the morning of April 29, Luis Lopez made his way from his apartment in Woodhaven, Queens, to immigration court at 26 Federal Plaza. This was his third trip to immigration court and he had amassed a number of papers, including his I-589 Application for Asylum form that he kept tucked neatly inside a manila folder protected under his arm.

The 61-year-old carpenter had been living in New York for a year, and he did not speak English. But today, he would represent himself in court and drop off the form that would dictate his future and act as evidence for why he should be granted asylum.

This was Lopez’s last chance to submit his claim before his one-year deadline of entering the U.S., after which he could be denied asylum and eventually issued a deportation order. For Lopez, that date was on May 1.

Also Read: He Found the American Dream on China’s TikTok, the Reality Was More Complicated

Lopez, who is from Ambato, Ecuador, arrived in New York last year. He has spent months looking for a pro-bono lawyer to help with his defensive asylum case with immigration court but was told by multiple organizations that they were unable to help him because they were at capacity. “I went to the hearings but I felt lost, not knowing the language or anything,” he said in Spanish, adding that every time he went he was told by the judge to return again. “My son told me that if I don’t file before May 1, that I would get deported,” he said. “That’s when I had to rush. I asked a friend, who knew English, to help me.”

In the past two years, about 200,000 migrants have arrived in New York City, many of whom have defensive asylum cases after submitting themselves at the border. But an exclusive analysis of data from the Executive Office for Immigration Review (EOIR) data shows that in 2023, roughly half of all immigrants appearing in the New York City’s largest immigration court at 26 Federal Plaza were unrepresented, with more unrepresented individuals in 2023 than the previous 5 years combined — the number tripled from 2021 to 2022 alone. The analysis was provided to Documented by Mobile Pathways, a tech nonprofit advancing equitable immigration access and support for underserved immigrants and partner nonprofits.

The analysis also shows that between 2022 and 2023, 55,039 immigrants with hearings at Federal Plaza lacked legal representation. Advocates say that New York City’s funding for pro bono legal services has not kept up with the demand, leaving thousands to navigate the complex immigration court system by themselves because they cannot afford private attorneys. Without representation, numerous studies have shown the likelihood of an individual being granted asylum, and being allowed to remain in the U.S. legally, is greatly reduced.

In 2019, a local gang attacked Lopez and injured his right leg, which required doctors to drill metal screws into Lopez’s bones, he said. After the attack, he spent several years hiding in eastern Ecuador. He decided to travel to the U.S. to seek asylum in February of 2023, in a journey that took three months. Lopez, along with his wife and step son, flew to El Salvador and made their way up through Guatemala, Mexico, and the U.S. by traveling in buses and cars — all while he was on crutches.

His brother, who had been living in New York for three years, flew the Lopez family to the city, and helped them find an apartment in Queens. “He helps me with the rent and sends me money,” Lopez said. He pays $1,400 a month from a combination of the money his brother gives him and funds that his step son is able to make by selling Ecuadorian treats — espumillas and quimbolitos — on Roosevelt Avenue in Jackson Heights.

While the money for rent compounds his stress, Lopez said that not having a lawyer to represent his family in immigration court is what feels most pressing. On April 25, he returned to his second immigration court hearing, once again without representation.

“I showed up and told him [the judge] that I don’t have a lawyer,” he said. “I told him that I called lawyers but they have too many cases and they don’t answer me.”

Lopez said the judge gave him another hearing date, and asked him to return with his asylum claim, the form I-589, ready to be filed — even if it was without a lawyer.

Lopez has also been looking for private immigration lawyers, but cannot afford their fees. He also hasn’t been able to find anyone at the immigration court who could look over his asylum claim, he said. “I am trapped, I don’t know what to do. I am a carpenter and I want to work, but I cannot.”

77,256 Hearings

According to the immigration court data obtained by Mobile Pathways, the number of individuals appearing at the 26 Federal Plaza immigration court has risen sharply in recent years.

In 2018, about 87% of individuals who showed up at 26 Federal Plaza immigration court had legal representation, the data shows. But five years later, in 2023, less than half of immigrants in court — approximately 46% — had a lawyer.

“That is a concerning drop because it’s fundamentally unfair when someone has to face deportation, face a government trained attorney, be subject to cross-examination by themselves without an attorney,” Rosie Wang, a program manager with Vera Institute’s Advancing Universal Representation Initiative, said about the data. The initiative works to provide publicly funded attorneys for detained immigrants, and campaigns for federally funded representation in immigration court.

The data also shows the total number of people with hearings in immigration court has grown substantially since 2018. That year 39,206 individuals had hearings at the Federal Plaza immigration court. But in 2023, the number of individuals with court hearings nearly doubled, reaching 77,256.

Currently, individuals do not have a right to counsel in immigration court as they would, for example, in criminal court. But numerous studies have shown that immigrants are more likely to win their cases with apt legal representation during their hearings. Data through April 2024 in New York immigration court shows that asylum was granted to 73% of individuals with legal representation, according to the Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse (TRAC) at Syracuse University. In contrast, asylum is granted only to 37% of the cases without representation. When immigrants are not granted relief in court, they often face deportation. So if individuals show up in immigration court unrepresented, “the consequences are far ranging and dire,” Wang said.

Advocates who spoke with Documented said a confluence of factors could be contributing to the drop in representation rates, including budget cuts that impacted programs like the Rapid Response Legal Collaborative, which provided legal assistance to newly arrived migrants. Legal providers were also already stretched thin before the pandemic and before high numbers of migrants began coming to New York in the spring of 2022.

“We’re very happy to serve them [recently arrived migrants], it’s just that organizations have had to catch up,” said Tania Mattos, the interim executive director of UnLocal, a community nonprofit helping immigrants connect to legal services, who has also been assisting newly arrived migrants with legal help. “It’s taken us a little bit to get up to speed.”

And as the number of people in immigration court has grown, so has the backlog. At the end of the 2023 fiscal year (Sept. 30), the immigration backlog stood at approximately 2.8 million cases, according to TRAC. But as of the end of April, the backlog reached more than 3.5 million cases — the highest it has ever been. And as the backlog has grown, the rates of representation have decreased nationwide, from 65% at the end of the 2019 fiscal year, to just 30% at the end of the 2023 fiscal year, according to TRAC.

Neil Agarwal, the principal data scientist for the Vera Institute Universal Representation Initiative, said that the drop in immigration court representation rates coupled with an “incredible explosion” in the immigration court backlog is a nationwide trend. Still, Agarwal said it was “impossible to keep up with the explosion in pending cases, which is the driver for these drops in representation rates.”

For immigrants living in New York City and appearing in immigration court, data shows that their chances of receiving deportation orders are high. In fiscal year 2024, from October of 2023 through March, judges issued the highest number of removal orders to immigrants who lived in NYC and appeared in immigration court, compared to other counties across the country, according to an April TRAC report. Only 13% of the immigrants residing in New York who was issued a deportation order were represented by an attorney, according to the report..

In response to the large number of migrants arriving in New York in the past two years and needing legal assistance, a group of organizations began to work together to form the Pro Se Plus Project (PSPP), an initiative to increase legal assistance for newly arrived migrants — with funding help from foundations, and the city and state.

More than half a dozen organizations work together on PSPP, helping migrants with asylum applications, Temporary Protected Status documents, change of address paperwork, appeals, and a variety of other needs, said Allison Cutler, supervising attorney at the New York Legal Assistance’s (NYLAG) Immigrant Protection Unit, who also runs the Pro Se Plus Project.

The group aims to prepare immigrants, including many asylum seekers, to represent themselves in immigration court when the day comes — or to set them up to find an attorney at a lower cost, since much of their application will be prepared with the assistance of PSPP. Though the individuals who attend legal clinics through the project won’t necessarily have an attorney represent them at the day of their hearing, NYLAG and other groups are organizing to provide what they view as the next best option in the absence of enough attorneys for every single person showing up to immigration court.

“The entire mission of the Pro Se Plus Project is to give those resources into the community and into their hands so that they don’t feel like they have to have an attorney to move forward with their case,” Cutler said. “Absent a right to counsel in immigration court, we’re always going to see individuals who do not obtain an attorney.”

About half of the people the project serves are staying in shelters, while others are renting rooms, or staying with family members, Cutler said. For newly arrived migrants, some unique considerations may apply to their cases. For example, those staying in shelters are subject to 30- and 60-day limits imposed by the city, and an additional hurdle is presented — with each change of address, it can become harder to track important hearing dates they must attend that are only sent through the mail.

From January through March, the project has trained over 150 advocates, provided advice and/or counsel to over 1,000 recently arrived migrants, and filed over 350 pro se applications, according to NYLAG. Through this initiative, the groups are able to reach a larger number of individuals than they would have been able to serve individually, Cutler said.

Wang called this kind of assistance “crucial,” but noted that it is part of a “stop gap” group of initiatives in the city and state’s emergency response for asylum seekers, and falls short of full representation. “The providers are doing the work, they’re meeting the needs where they can and trying to grow that capacity but there’s more of an investment needed,” Wang said. “Realistically we know that at this very moment there’s simply not the number of lawyers and representatives available to represent everyone.”

Groups like Vera and NYLAG have been for years urging the New York state legislature to pass the Access to Representation Act, which would secure the right to legal counsel for anyone going through proceedings in New York state immigration courts. But some advocates are concerned that even that may not be enough. “We do need universal representation legislation, but I’m afraid even then, there are just not enough attorneys for the amount of people that are out there,” said Mattos, from UnLocal.

TestPost3

On a recent Wednesday morning on the 12th floor of immigration court at 26 Federal Plaza, the large majority of individuals who had scheduled hearings did not have an attorney listed for them on the docket posted in the hallway. Families rushed in and out of the elevators, looking to make it to the first hearings of the day, which began at 8:30 a.m. For many, it was likely the first time that they would stand in front of an immigration judge — and without an attorney.

Angelica Ben, a 23-year-old migrant from Guatemala was one of those who would face an immigration judge without a lawyer that morning. She had been in New York for about eight months, and had received a Notice to Appear in immigration court for May 8.

Ben said she had been directed to various lines around the building and she wasn’t sure where to even enter to get to the court. It was already approaching 9:30 a.m., and her hearing was supposed to begin at 8:30 a.m. “I showed them the papers, they [security] tell me to go here, to go there,” she said as she stood outside the building.

Ben also hasn’t been able to find a lawyer yet for her case, and hasn’t been connected to any legal clinics or services, Ben said. After her hearing, Ben said she received a list of pro-bono legal service providers to call, so she would see if any had space for her. “I don’t know what to do,” she said. “I’m really lost.”