It was already dark when Mayor Eric Adams and his security detail pulled up to the curb of the Wyndham Garden, a drab hotel next to a strip mall in Fresh Meadows, Queens.

At the time, his administration was paying for the hotel to shelter more than 100 formerly incarcerated New Yorkers integrating back into society after their release.

But the mayor wasn’t here to check in on one of his criminal justice initiatives. On that November evening nearly two years ago, Adams was visiting Winnie Greco, a top mayoral staffer, who had recently moved into one of the rooms at the Wyndham Garden.

Adams got out of the car, walked through a side door and went up to Greco’s specially arranged suite on the 11th floor, according to two sources with knowledge of the visit.

The mayor had been to the hotel before. Its owner, Weihong Hu, had thrown two campaign fundraisers with Adams present when he was running for mayor in 2021. Now Hu, who was reaping millions of dollars in city business through this very facility, was housing Greco in a room paid for by taxpayers, business and government records obtained for this story show.

Greco ended up staying at Hu’s hotel for more than eight months, initially as she recovered from surgery, according to two sources with knowledge of her stay.

The lodging arranged for the mayor’s advisor is just one facet of a mutually beneficial relationship between Adams, an aggressive campaign fundraiser, and Hu, an ambitious hotel operator who bundled tens of thousands of dollars in campaign checks for his mayoral campaign and subsequently scored behind-the-scenes benefits and millions in contract dollars from his administration, an investigation by THE CITY, The Guardian US and Documented reveals.

The details of how this relationship blossomed in the odd setting of a hotel-turned-shelter offer a rare window into the way transactional dealings have taken shape in the Adams era.

This report is based on a review of thousands of pages of city and business records and interviews with more than 20 of Hu’s former associates and current and former government officials. Nearly all sources spoke on the condition of anonymity citing fears of retaliation from Hu or the administration. Several provided reporters with photos, text messages, emails and videos to back up their claims.

In Hu’s case, multimillion-dollar city-funded contracts to her companies’ hotels continued to flow as she befriended a tightly knit core of the mayor’s longtime associates, some the subject of law enforcement investigations and ethical controversies who multiple sources say pledged to go to bat for her with city agencies.

It was at a 2021 fundraiser with Adams at her hotel that Hu became acquainted with a longtime pal of the future mayor, John Sampson. Formerly a state senator, Sampson had been released from federal custody only a month earlier, after being sentenced to a five-year prison term for trying to obstruct a probe investigating allegations that he embezzled more than $400,000.

Hu named Sampson as CEO of one of her hotel companies in early 2023, and, according to a former city official familiar with the situation, he committed to helping her land a lucrative contract for a migrant shelter at a hotel she operates in Long Island City, Queens. A month later, the Department of Homeless Services approved a city-funded migrant contract slated to disburse $7.5 million annually to the hotel.

Hu also enlisted the help of another trusted Adams advisor, Rev. Alfred Cockfield II, whom she introduced to colleagues as a “consultant,” according to one former associate who said he attended business meetings with Hu and Cockfield. The former associate and another source with direct knowledge of the matter said Hu enlisted Cockfield to help her reverse city orders halting construction at two major hotel developments in midtown Manhattan.

Cockfield is a politically wired pastor who, after Adams won the mayoral primary, launched a political action committee, Striving for a Better New York, which he told Politico was intended to uplift “moderate,” “pro-business” candidates in the Adams mold.

“The work I’m doing is God’s work,” he said.

Yet campaign finance records show the PAC paid Cockfield $144,000 in wages and consulting fees — many times more than what it ever gave to an individual candidate. It also gave $60,000 to a charter school Cockfield leads. Last year, the school returned the entire sum after the state’s Division of Election Law Enforcement sent inquiries to the PAC about some of its allocations.

The mayor’s son, Jordan Coleman, dressed in black and pushing a roller suitcase, and an unidentified woman also stayed in a room in November 2022 at the Fresh Meadows hotel where Greco was staying, according to a former worker at the hotel. That room, too, was among the 148 paid for by taxpayers.

Coleman hung up on a reporter and didn’t respond to text messages seeking comment. In a phone call, Hu’s attorney, Kevin Tung, denied that the mayor’s son stayed at the hotel overnight, but said he may have visited to discuss business with Greco, who has at times accompanied him to events.

The administration’s largesse flowed back to Hu in a variety of ways, the investigation’s findings show. After Adams came into office, his administration authorized the renewal of Hu’s six-month shelter contract at the Fresh Meadows hotel four times, reaping her business $6.2 million a year in income.

It also finalized a second contract sending $6.3 million a year to Hu’s hotel in Long Island City, despite a history of elevator breakdowns and minimal housekeeping detailed to reporters by former workers and claimed in court documents.

Last year, the Department of Homeless Services twice approved a more lucrative arrangement for the Long Island City hotel, bumping its annual potential revenue to a total of $8.8 million, government records show.

The help a close Adams ally can offer was evident on two occasions in which, according to sources, Hu tapped Cockfield for assistance with city authorities.

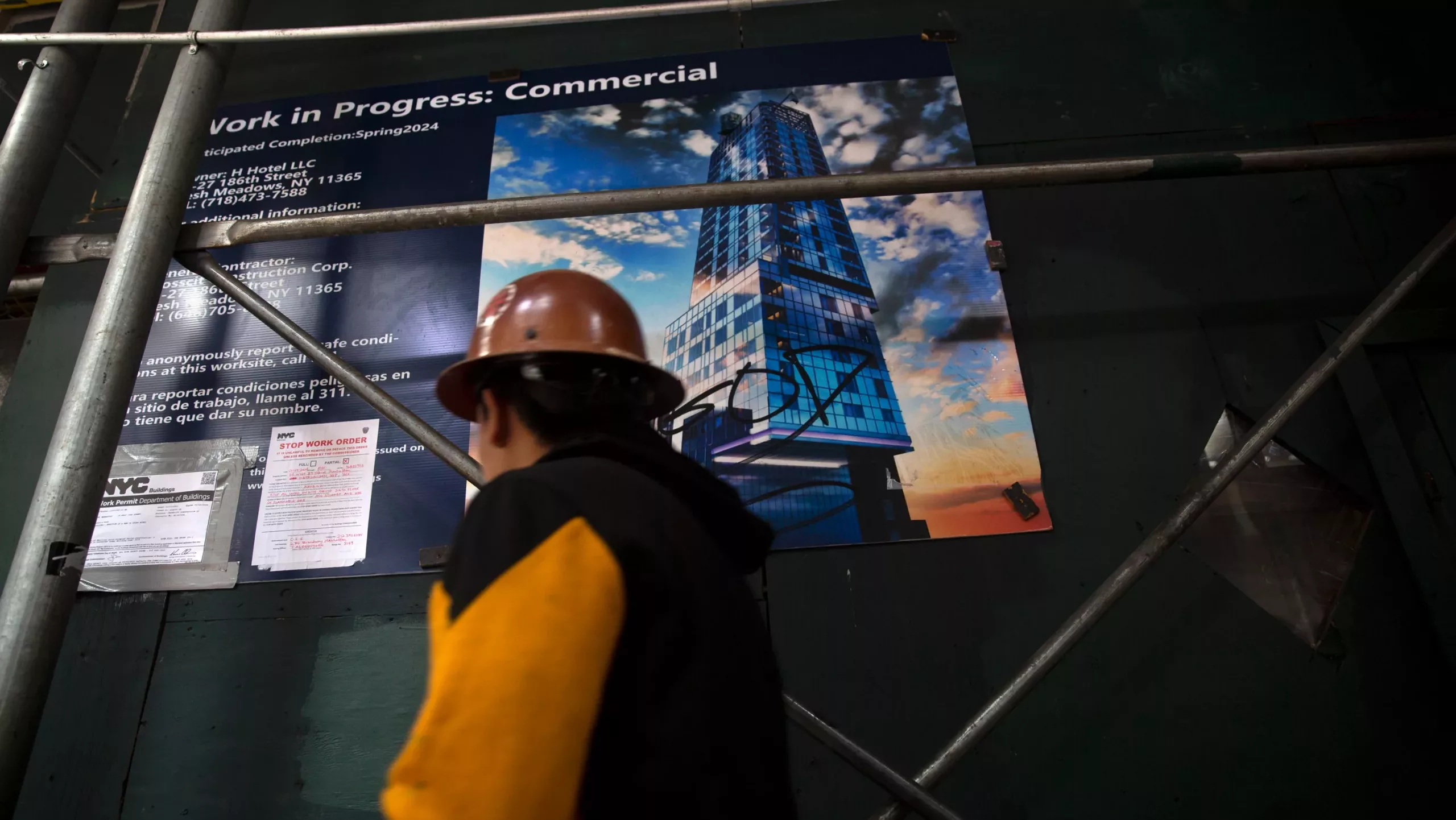

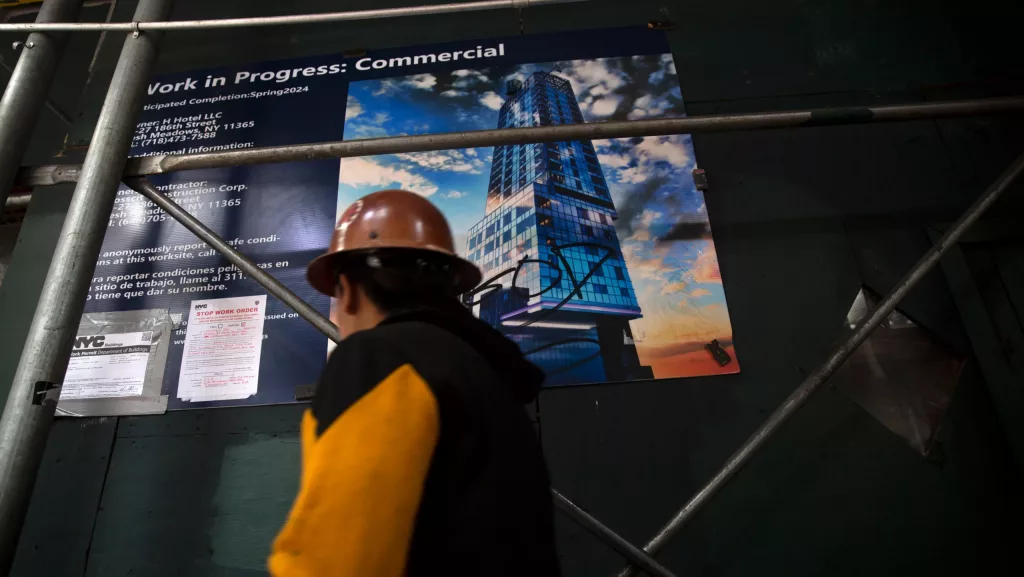

After a building inspector halted construction at one of her hotel developments, near Bryant Park on West 39th Street, citing a serious safety issue, the minister made a late-night call to top Department of Buildings officials and urged them to allow construction to proceed, according to a source familiar with buildings department operations.

Roughly an hour later, the agency reversed the stop work order, which department records show was lifted just after 11 p.m.

At the second hotel development, Hu retained Cockfield to help lift a city Department of Buildings stop-work order issued after Hu’s team had begun an illegal demolition of rent-stabilized apartment buildings on West 35th Street in Manhattan, according to a source who said he attended meetings with Hu and Cockfield about the situation. That source said Cockfield and another individual he couldn’t identify promised to call city agencies on the hotel owner’s behalf.

In late 2022, the Department of Buildings gave Hu permission to resume construction on that site, approving a plan that ignored a previous commitment to neighborhood leaders and the city’s housing agency to preserve affordable apartments.

‘What Happened Here?’

The decisions at both sites left people familiar with the situations surprised and suspicious that political favoritism was at work.

“Somebody had to get a favor somehow somewhere on this because this went from an incredibly public, structured process with multiple agencies involved to come up with a solution, and then it all went away,” Joe Restuccia, a longtime housing activist and Manhattan community board member, said regarding the DOB’s reversal on West 35th Street. “What happened here?”

Both the Adams administration and a lawyer for Hu defended their actions.

In response to questions from THE CITY, The Guardian and Documented, Adams’ office stood by the Department of Buildings’ oversight of Hu’s two hotel development sites.

“The two projects referenced went through standard DOB processes for investigating and addressing complaints, and once all conditions were deemed safe at each site, DOB allowed work to continue,” said mayoral spokesperson Liz Garcia.

Garcia blamed Hu for walking away from discussions with HPD about preserving the affordable housing, but said the developer’s subsequent compliance with zoning regulations — following changes to rules governing hotels that were pushed through by the outgoing de Blasio administration — gave the buildings department “no choice but to allow construction to move forward.”

Tung, Hu’s attorney, said he didn’t know the details of an affordable housing agreement but that he remembered the negotiations.

“It never got down to contract level,” he said. “It was only talking, talking.”

Neither the mayor’s press office nor Tung produced receipts to back up their previous statements to THE CITY that Greco paid for her stay in Fresh Meadows. An analysis for this article of hotel blueprints and invoices show that for a period of as long as eight months, the city was being billed and paid for Greco’s room at a cost that likely came to $50,000 or more.

Greco didn’t respond to a phone call and text message seeking comment.

On Wednesday, the mayor’s press office declined to comment on Greco’s stay, citing an existing Department of Investigation probe of possible ethical violations by her. Regarding Coleman’s reported stay, it pointed to comments Adams has made previously about how he doesn’t get into his son’s personal business.

In a phone call, Tung strongly defended his client’s record concerning Greco’s stay and other issues. “All of these are allegations, allegations, and most of them, I don’t think they’re true,” he said.

He acknowledged that Hu hired Sampson as CEO of one of her companies. At first, the attorney denied that Adams’ ally worked to help secure a contract with the city for Hu, but subsequently said that he did not know if he did.

Tung stated that Cockfield approached his client and offered her his services, but argued that Hu never hired or paid the minister. Tung said he did not discuss the alleged Department of Buildings call with his client.

Cockfield declined to comment on what role he played for Hu and didn’t respond to questions sent by email about his alleged work in getting the stop work orders lifted or on the state’s enforcement action against the PAC he founded.

Sampson didn’t respond to detailed written questions about his role that were left at the front desk of Hu’s corporate office in midtown. But in a brief interaction with a reporter outside the office, Sampson said, “I’m not saying anything. I’m just saying, ‘Do your homework.’ I’m not going to do your homework for you. You know I don’t deal with the press.”

A Backroom Introduction

Adams and Hu first met in the wood-paneled back room of the Park Plaza Diner in downtown Brooklyn on May 10, 2021, according to two people who were present.

Adams’ interest in the meeting was straightforward. The Brooklyn Borough President, then in his eighth and final year, was in the thick of a hotly contested Democratic primary for mayor and needed to bolster his campaign warchest as he began to break from the pack.

Hu’s interest was also transactional, according to one of her former associates. The successful hotel developer had cultivated strong contacts inside the de Blasio administration, from which she had secured multi-million dollar shelter contracts for the two Queens hotels. Now, to keep the gravy train rolling, she needed a new ally in City Hall.

The two came from opposite sides of the globe. But they shared the ambition that comes from being self-made. Adams grew up in working-class Queens, turning himself from a transit cop to a state legislator to Brooklyn’s borough president. Hu, who came of age in China, started off as a food vendor and eventually transformed herself into a prosperous hotel developer, according to internet postings disseminated by Chinese authorities.

But local prosecutors in China allege that on at least one occasion she sought to advance by means that went beyond just playing politics. According to an archived article published by a Chinese local government website, Hu was detained sometime around 2007, just before she could board a plane to the U.S. The article states that she “confessed” to paying “millions in bribes” to a Communist Party official as part of an investigation into a state owned company.

A separate account on a Chinese state website refers to a local developer named “Hu” who gave a gift of cash to a high-ranking Communist Party official, and later convinced the official to use his position in the same state-owned company to buy out her share of a joint real estate project at a vastly inflated price.

The official was later sentenced to life in prison following multiple bribery allegations.

Tung said that Hu denied being arrested or engaging in bribery in China. “Mrs. Hu went back to China recently,” he said. “If she had been arrested, and she escaped, she wouldn’t be able to go back.”

At the half-hour meeting at the diner, Hu did not delve into her past in China. She had pressing business concerns in New York.

With de Blasio soon exiting office, there was no guarantee that a new administration would extend her hotel shelter contracts. Nor would it necessarily help her reverse the stop work order that the buildings department had recently imposed at her hotel construction site on West 35th Street.

So on that day in the backroom of the Brooklyn diner, Hu and a few of her associates sat down with Adams, who was accompanied by his 23-year-old chief fundraiser, Brianna Suggs. The mayoral hopeful pitched himself as the anti-crime champion and praised Hu’s entrepreneurial endeavors with catchphrases like, “That’s the American story” and “Immigrants built New York City,” the same source recalled.

Hu didn’t say much, according to one attendee there that day, but repeatedly called the candidate she had just met “a good man.”

At the end of the meeting, Hu and Adams posed together. The candidate grinned. The businesswoman, buttoned up in a striped suit, stared straight into the camera. Then the future mayor walked out of the diner with his fundraising liaison.

The breakfast lasted just half an hour. But that had been enough. Three weeks later, Hu began bundling thousands of dollars in campaign contributions for her new candidate.

Lobster and Purple Potatoes

On June 3, 2021, weeks before the Democratic primary, Hu invited Adams to the Fresh Meadows hotel.

That evening, Adams and Suggs walked through the side door and took an elevator up to the penthouse Hu shared with her husband and business partner, Xiaozhuang Ge. There, according to two attendees, Hu’s staff offered Adams and his team red wine, an array of noodle dishes and stewed lobster.

The mayor discussed his proposals to combat anti-Asian hate crime and speed payments to city contractors, one source recalled. Then, according to that source and another attendee, Hu’s assistant handed a pile of checks to Suggs.

How much the event brought in is difficult to determine because the Adams campaign did not report Hu’s fundraiser to the city Campaign Finance Board. A spokesperson for the mayor’s 2021 campaign didn’t respond when asked about the reporting lapse.

But public records show that a day later, the Adams campaign took in $34,000 from 17 people who each gave $2,000. The campaign finance records show that numerous contributions of that amount — $100 below the maximum permitted — went to the Adams campaign around the time of this and subsequent Hu fundraisers. These donors included one of Hu’s former business associates and a former commercial tenant in another Queens building she owned.

Adams eked out a victory in the Democratic primary a few weeks later, effectively making him the mayor-in-waiting that year.

That September, Adams went back to Hu’s hotel for another fundraiser. This time, the hotel developer served fresh lobster and purple potatoes on the hotel’s third floor, according to two of the diners.

One of the guests at the candidate’s table was John Sampson, who Adams had known at least since their days together in the state Senate when they were both embroiled in a state contracting scandal. While both maintained their innocence, many Democrats in Albany turned on Sampson, who lost his leadership position with the senate’s Democratic conference.

Adams stayed loyal to him, and he to Adams. In November, Sampson was spotted among the guests at Adams’ raucous victory party in Brooklyn following the general election.

That same month, a federal judge thwarted Sampson’s bid to attend the city’s biggest annual political junket, the Somos Conference in Puerto Rico. In harsh terms, she rejected the travel request and questioned Sampson’s employment at the time by Exodus Transitional Community, a nonprofit that was running the post-incarceration program at Hu’s Fresh Meadows hotel.

“The Court is not at all convinced that his employment and rapid promotion at Exodus is appropriate,” Judge Dora Irizarry wrote on November 2, 2021. “While he allegedly is not involved in procuring contracts, he is involved in seeking property for the program, which is completely related to his criminal conduct involving his misappropriation of funds as a referee for the state court in forfeiture proceedings.”

Those concerns did not stop Hu from making Sampson her corporate CEO in early 2023, according to two sources. One said Sampson assured Hu that he’d get her another city contract at her Long Island City hotel after Exodus departed as the service provider in late 2022 amid multiple investigations into its work.

A Call to Adams Officials

Seven months after Adams took office, Hu’s proximity to the mayor’s inner circle proved its value, according to a source familiar with Department of Buildings operations.

On the morning of July 8, 2022, an inspector showed up for a surprise visit at the large lot across from Bryant Park where Hu’s firm was erecting a 34-story hotel. The safety expert walked onto the construction site and peered at a crimson hoist Hu’s team was using to lift workers and equipment hundreds of feet into the air, Department of Buildings records show.

What he saw sparked safety concerns — an assessment that an administrative court substantiated a few weeks later when it found that the hoist did not comply with the site’s approved plans and presented “an immediately hazardous condition.”

The design plans called for two squat columns anchored in a solid concrete slab to serve as a safety cushion for the hoist. Instead, the inspector saw, the columns were several feet in the air resting on an improvised structure of metal beams and poles, according to site photos obtained through a public records request.

Worried that the unapproved assemblage might not be able to hold the weight of the hoist, as the inspector would later testify, he stopped all work above 75 feet.

At this point, Hu could have followed the department’s lengthy guidelines for clearing such an order, which require builders to make changes, attest to their fixes in sworn statements and request a re-inspection, a process that can take weeks or months.

But she went another way. Her team contacted the Department of Buildings, and soon the agency swung into action.

In the hours that followed, the agency sent multiple inspectors to the site throughout that afternoon and early evening, according to public records and interviews with two people on the site that day. But despite the efforts of Hu’s construction team to fix the structure, the inspectors were not satisfied. They would not clear the safety violation.

“They come back, they go back to their car, call their supervisors, and come back again,” said one source, who said that he left the job site around 8 or 9 p.m. with the issue unresolved.

But the day wasn’t over. Around 10 p.m., Cockfield called two top Department of Buildings officials and urged them to lift the order, according to the source familiar with DOB practices. Just after 11 p.m., the department rescinded the stop work order.

At the time, the Department of Buildings was run by Eric Ulrich, an Adams appointee who was later indicted on bribery charges. Ulrich has pleaded not guilty. He didn’t respond to a request for comment.

The Adams administration didn’t directly respond to questions about Cockfield’s alleged phone call, but said the DOB wouldn’t lift a stop work order without proper documentation from the owner.

Buildings spokesperson Andrew Rudansky said that the agency reversed the stop work order because the builder had fixed the improperly constructed hoist, removing any safety concerns. He said the department responds to requests for reinspections of stop work orders from contractors in one to two days on average, and said that the department would “continue to hold this contractor to the same high safety standards we expect everyone to meet if they want to build in our city.”

But three New York City construction experts said the events that day suggested that Hu’s project got special treatment.

A data analysis for this project shows that roughly one half of one percent of the roughly 7,000 stop work orders issued and reversed in 2022 were voided the same day. The median length of time for them to be resolved was 35 days.

“There’s a procedure that we have to follow for a work stop to be reinstated, and that’s filling out a certificate of correction and requesting a reinspection in an agency form,” said one person familiar with department procedures, speaking on the condition of anonymity. “There’s a lot of work stops in the city. It’s like skipping in line.”

Vanishing Apartments

Hu also tapped Cockfield to help her erase the stop work order on West 35th Street, according to a source who attended strategy meetings with the minister. This time the arena was a site with a tortuous history that pitted Hu’s dream of developing a 25-story hotel in Manhattan’s Garment District against a community bent on preserving two small apartment buildings that had long housed residents of modest means.

For six years under the de Blasio administration, the city’s Department of Buildings and Department of Housing Preservation and Development (HPD) worked in concert with the local community board to insist that Hu preserve more than a dozen affordable units that she sought to take a wrecking ball to.

The dynamic changed when Adams took office in January 2022. Hu began strategizing not only with her architect and a buildings code expert, but also with Cockfield and another consultant, according to a source who attended meetings on the project.

Before Adams’ first year in office ended, Hu got her wish: She didn’t have to build any affordable units. The Department of Buildings approved a plan for a fully commercial 25-story hotel.

It was an unlikely outcome in a district that has some of the city’s toughest zoning rules protecting rent-regulated apartments, policed by an engaged community board.

Hu waded into this environment in 2016, when she bought the century-old buildings at 317 and 319 W. 35th Street for $28 million.

She immediately filed plans with the Department of Buildings to knock down the structures, sending Community Board 4 into an uproar.

Nonetheless, the community board, led by its housing expert, Joe Restuccia, worked for years on a compromise plan that would allow Hu’s project to go forward so long as she preserved the affordable units for the neighborhood.

This culminated with a letter Hu wrote to the city’s housing agency in early 2019 outlining a plan to provide more than a dozen affordable apartments in her project.

With the letter written, the community board assumed its role was done.

That’s why Restuccia, a veteran affordable housing developer with a white mustache and the bark of a former tenant organizer, was stunned when he got an email from a local resident two years later informing him that the facades of the two residential buildings “have been demolished & removed.”

In a photo attachment, Restuccia said he could see that the wooden floors of the century-old dark brick buildings had been destroyed and replaced.

In response to the board’s alarm, the DOB issued a stop work order blocking all construction at Hu’s site as of March 4, 2021.

It was another seeming victory for the board. Restuccia figured the city would freeze Hu’s project until she followed through on the intentions she had expressed to the housing department.

But according to two sources familiar with the matter, Hu was dead set against building affordable apartments — and when the work stoppage continued into the Adams mayoralty, she began the strategy sessions with her team of experts, along with Cockfield and her other consultant.

In those sessions, Hu had her architect lay out the bureaucratic hurdles they faced in getting the stop work order lifted. Cockfield and the other consultant took notes, asked questions, and promised to call decision makers in the Adams administration, according to the source who attended the meetings.

That summer, Hu’s architect submitted a new plan to the Department of Buildings that upended everything that had been agreed to. The hotel was now going to be entirely commercial without any affordable apartments.

The Department of Buildings approved Hu’s permit to build as she wished, and in November of that year, the agency lifted the stop work order that had stretched on for 18 months.

The agency gave no notification to the board or local elected officials, some of whom say they were stunned by the turn of events.

Rudansky, the DOB spokesperson, echoed City Hall in saying the developer’s adjustments to the project in 2022 allowed it to meet all the district’s zoning requirements and other regulations. He said HPD had issued the site a certification of no harassment, which indicated to the DOB that the project complied with local zoning provisions.

But a spokesperson for HPD confirmed the agency had yet to take several actions that Restuccia said were mandated by zoning rules to make a project compliant.

Rudansky also pointed to 2021 changes in city permitting for hotels that he asserted overrode the obligation for Hu to provide housing. But Restuccia took strong exception to that, saying that the only reason that Hu had won an exemption from more stringent permitting requirements in the first place was because she had committed to preserving the affordable housing.

He was joined in his criticism by Councilmember Erik Bottcher (D-Manhattan), whose district includes the site of the proposed hotel.

“It’s hard to understand why the city would decide to move forward with a project that removes affordable housing units from its scope at a time they are desperately needed,” Bottcher said. “We must have a full account of what happened here and understand how this project departed so far from the original plan, which was meticulously worked out by my predecessor, Community Board 4, DOB and the property owners.”

From Hubei Province to Hudson Yards

On the evening of June 9, 2023, Weihong Hu was standing in a common space at her new home, a shimmering 92-story glass skyscraper in Hudson Yards. She had recently paid $5 million for a condo there, a short walk from the rent-stabilized apartments she had eliminated to make way for her hotel on 35th Street.

That night she hosted a gala fundraiser for Adams, who was now running for re-election. Hu and the mayor both wore blue suit jackets and posed for photos. Their mutual friend Winnie Greco, sporting a bright pink dress and pearl necklace, trailed the mayor closely, as guests helped themselves to noodles and sushi.

“We want to start early and make sure that we have the necessary funds to put on a good strong campaign,” Adams told the assembled supporters, his hands clasped just above his suit buttons.

On the day of the fundraiser and over the two days that followed, the Adams campaign reported receiving 20 campaign contributions, all exactly $2,000 apiece. Adams’ reelection campaign team declined to say how much it received from Hu’s event. But many of the donations that day came from Hu’s family’s friends and associates, three of whom would later allege that they had been illegally reimbursed by Hu’s family.

The sumptuous setting, enclosed by large windows that revealed the bright lights of the West Side skyline, was a world away from her previous homes in Hubei Province and her hotel-turned-shelter in Queens.

Still, Hu continues to seek new opportunities.

Two weeks after the fundraiser for Adams, she registered as the new CEO of a long-dormant not-for-profit called Urban Purpose for Community Affairs.

The entity’s registration paperwork makes clear that Hu wants to go beyond renting out her hotels to city-contracted social service providers. She wants the social service contracts too.

Her group has submitted a proposal to run a program housing asylum-seekers, the Department of Homeless Services confirmed.

TestPost3

The not-for-profit’s original board members, who started the group 13 years earlier, have all moved on.

In their place, the paperwork lists, among other associates, Hu’s son, her daughter-in-law, her lawyer’s law partner, and the sister of Adams’ longtime friend John Sampson, her corporate CEO.

Additional reporting by Katrina Northrop/The Wire China.