This story is supported by HomeLab NYC at Incite and the Toni Stabile Center for Investigative Journalism.

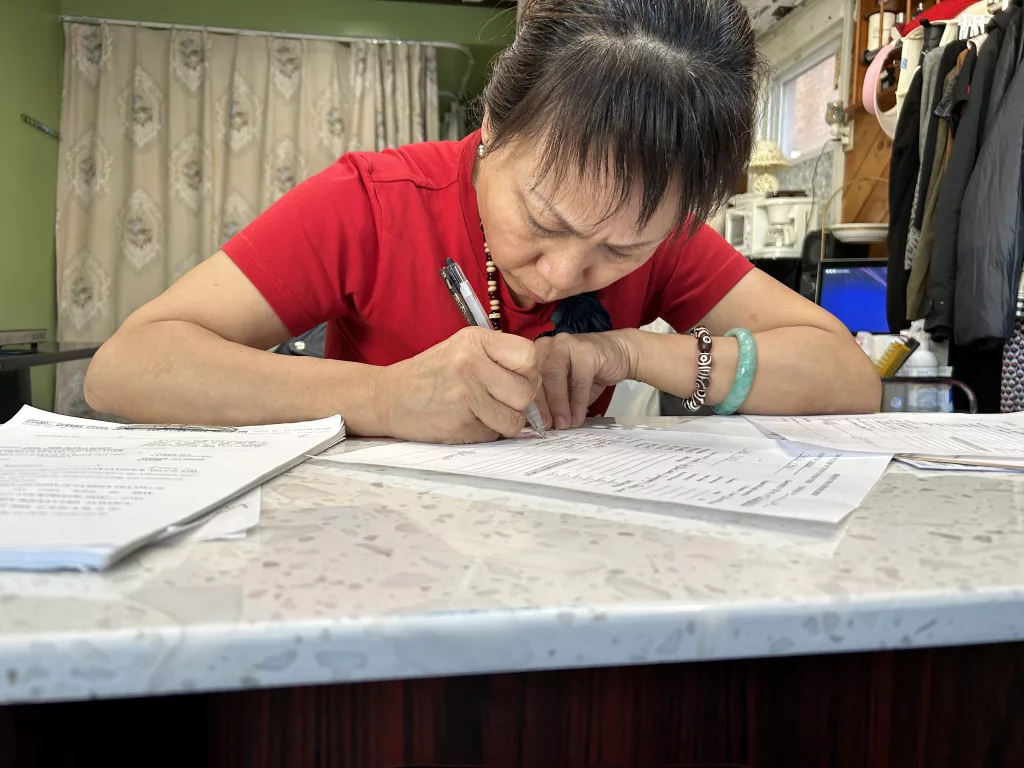

At 61, Zhulin Chen had achieved a version of the American dream last summer: She had finally saved up enough to open up her own beauty salon in Queens, eight years after moving to the U.S. from her native China.

But in August, despite having a signed rental agreement for her apartment in Flushing, Queens, she was unexpectedly locked out of her home by Hui Ji and Zhao Hang Jia, who had been renting her the room. She was forced to navigate Queens Housing Court in an attempt to move back in and gather her belongings. (In court, she learned that Ji and Zhao were actually also tenants of the apartment and had been subletting it to her. Ji and Jia did not respond to requests for comment.)

Also Read: How NYC Protects Against Job And Housing Discrimination

Chen doesn’t speak English and has been able to earn a living in New York City, taking jobs handing out flyers and waitressing, using Mandarin and a language dialect called Fuzhou. She represented herself because she couldn’t find free legal services or afford her own lawyer, she said.

Following a hearing in October, Queens Housing Court Supervising Judge John Lansden, who was presiding over her case, ordered the landlords to allow Chen back into her room. But upon her return, Chen found the wall of her sublet room had been torn down and her belongings removed. Ji and Jia’s response to her protests was dismissive, urging her to sue them again.

Court staffers and volunteers then helped Chen file six motions to hold her landlords in contempt, without Chen knowing what the word “contempt” meant.

However, the judge in her case denied all of Chen’s motions because of “improper service,” which included sending her motions by certified, instead of regular, mail and sending the letter one day late.

Chen said she mailed the motion in the wrong way because no Mandarin interpreter had explained the instructions on the document; instead, she used her translation app to get help from a clerk in the courthouse. The letter was one day late, Chen said, because she had spent a long time filling out the form without the help of an interpreter. And it was too late to travel from Jamaica to Flushing, where the post office had Chinese-speaking staff who could help her.

After four months of unsuccessful fights in Housing Court, Chen had moved into a homeless shelter by January.

“They’re really screwing me in court,” she said in Mandarin in the hallway of the courthouse on Feb. 1. She had been told yet again that her motion against her landlords was denied.

For those like Chen, who is one of many Chinese tenants in New York City’s housing courts who have limited English speaking skills, the lack of language support in court means they suffer financial loss, emotional stress and, sometimes, the avoidable loss of their homes.

Over the past several months, Documented, HomeLab NYC and Columbia’s Toni Stabile Center for Investigative Journalism have observed dozens of Chinese-language Housing Court cases and have spoken with more than a dozen tenants, attorneys, judges and interpreters about the issues they encountered when the assistance of a court interpreter was required.

Those interviews and a review of court, staffing and budget documents reveal a language support system that is underfunded and relies on a handful of overworked and underpaid interpreters, many of whom haven’t received training for years. The performance of Housing Court interpreters is also not regularly assessed by supervisors who understand Mandarin, and the form to make complaints is also not available in various languages.

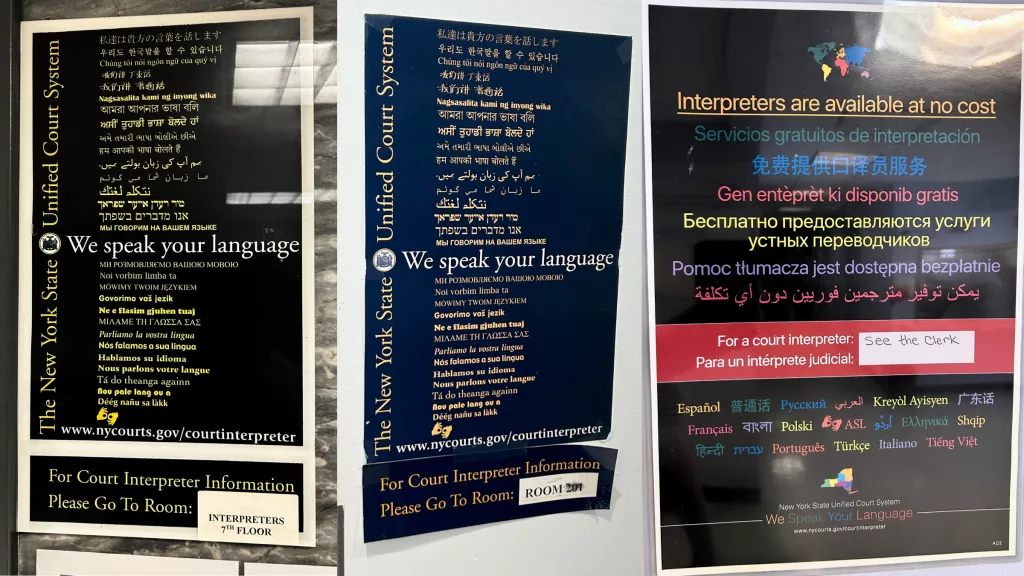

The New York State Court System states that it will inspect courthouses regularly to ensure that multi-language signage is in place and will provide correct information. Still, multiple visits to different housing courts found Chinese tenants could easily get lost in courthouses because there are not enough Chinese-language signs.

‘One courtroom at a time’

Mandarin is the third most widely spoken language in the court system, after English and Spanish. The City Court, which contains Housing Court, recorded 2,333 cases requiring a Mandarin interpreter in 2023, the highest number of such cases in the past five years.

Yet the number of full-time Chinese interpreters in Housing Court has not increased from five years ago, despite repeated demands from advocates and litigants for more interpreters.

In 2019, there were seven full-time Mandarin interpreters in the five boroughs’ housing courts. In 2023, that number had dropped to five full-time interpreters. At one point in 2022, there was just one full-time Mandarin interpreter for all five housing courts, according to the court’s data listed on the NYS Unified Court System website.

Wesley Wang, a spokesperson from the Office of Language Access, could not confirm the number of Mandarin interpreters currently employed at housing courts.

A housing court interpreter, who wished to remain anonymous for fear of retaliation, told Documented that in 2019, 2022 and 2023, three full-time and one part-time Mandarin interpreters were employed by the court system. Court interpreters in New York state are either court employees or per diem interpreters, who are paid on a daily basis.

“The court system is conducting court interpreter testing and has also been working vigorously, stepping up recruitment and outreach efforts to address court interpreter staffing shortages — due to retirements and relocations, some spurred by the pandemic, among other factors — as well as fill other critical job titles,” Alfred Baker, the State Office of Court Administration spokesperson, wrote in an email to Documented.

Baker also did not confirm the number of full-time Mandarin interpreters after numerous requests from Documented.

Also Read: New York’s Dire Need for Indigenous Interpreters

The insufficient number of housing court interpreters has also increased their workload, according to the interpreters themselves, resulting in interpretations of substandard quality.

“There has always been a shortage of interpreters, mainly because supervisors don’t want to spend money on recruitment,” said one interpreter, on condition of anonymity for fear of retaliation. The interpreter said he usually has more than 10 cases a day in one of New York City’s civil courts. These cases include not only housing cases, which fall under civil court, but also general civil cases and small claims.

New York state courts are mandated to provide interpreting services at no cost. This commitment to language accessibility is also outlined in the Court Interpreter Manual and Code of Ethics of the state court system, which ensures that everyone, regardless of their English proficiency, can fully participate in legal proceedings within New York’s courts and court agencies.

Although some litigants said they had no trouble getting an interpreter, seven out of 11 of the litigants and attorneys that Documented spoke to said they often have to wait longer than English-speaking litigants for their cases to be heard.

Baker, the spokesperson of the court system, said in the email that there may be a wait time as “interpreters can only provide language access in one courtroom at a time” and that the problem is not exclusive to those who need a Mandarin interpreter.

Sometimes they cannot get an interpreter at all.

On Jan. 24, 2024, for example, there was not a single Mandarin interpreter in Manhattan Housing Court. In one hearing, for a tenant named Hok Thu Chan, Judge Daniele Chinea said all the Mandarin interpreters were sick. Chan had to have his son translate for him, and added that the court didn’t ask for a per diem Mandarin interpreter even though the judge knew all full-time interpreters were absent that day.

Even on days when interpreters were available, “we have to wait until the end to be heard in every court appearance,” Chan said. The long wait times meant the son needed to take a full day off work, resulting in missed income.

One reason for the shortage is likely the low pay. The state’s court interpreters’ salary range is $60,245 to $86,000 according to a 2023 report, nearly 35% less than that of the court reporters who transcribe court hearings. Federal court interpreters get paid anywhere from $120,000 to $157,000, surpassing the earnings of federal court reporters, court clerks and court officers. Per diem interpreters are paid $220 for a half-day and $385 for a full day of work in New York state.

The state’s fiscal year 2025 budget is allocating more funds to pay for additional judgeships and support staff in housing courts. A $7.5 million increase is planned in the housing portion of the budget. Of this, $5.7 million has been allocated for additional judgeships; the Housing Court’s budget makes no mention of interpreters at all.

“The people who need language access services are often those who don’t have power,” said Sateesh Nori, an attorney who has represented tenants for over 20 years for the Legal Aid Society of New York City and a New York University law professor. This is the main reason, he said, why language access problems have not been addressed.

Issues with interpretations

Court interpreters are mandated to “faithfully and accurately interpret what is said without embellishment or omission.” However, many interpreters failed to provide accurate interpretations, Documented found.

In Chen’s Feb. 15 hearing, an interpreter inaccurately translated “tens of thousands of dollars’ worth of goods” into “hundreds of thousands of dollars’ worth of goods.” Another court interpreter seemed to have trouble coming up with the English word for “shelter,” taking more than 10 seconds to find the word during a Feb. 7 hearing.

Also Read: Asian Immigrants in NYC: Where To Find Legal Help, Education & Community

In a Dec. 12, 2023, hearing in Queens Housing Court, Jei Jan Wu, a tenant who sued her landlord, for harassment, stated in English: “He will use every way to torture you since he knew I am only a sick old woman there alone. I don’t have family or friends who can come over; can punch him. He bullies me every way he wants.”

The interpreter said in Mandarin that this meant: “Since he/she didn’t have any friends or relatives on his/her side. If he/she did, he/she’d be eager to come over and teach her/him a lesson.”

Because “he” and “she” are pronounced the same in Mandarin, the interpreter’s translation can be understood in two different ways. But neither option completely conveyed Wu’s version of events. In addition, the interpretation was not done in the first person, which violates the interpreter’s manual.

During this hearing, the interpreter did his work remotely and omitted some portions of the testimony from his translation.

Nori said that omissions during interpretation may leave out critical information. “The judge might have offered A, B, and C to the litigant, but he could have offered A, B, C and D,” he said. “We don’t know what we have missed, that’s the most horrifying part.”

The state’s interpreter’s manual allows for remote interpreting. But some judges don’t like it. “Virtual court appearances with interpreters create a serious issue of access to justice,” said Jack Stoller, supervising judge for the Housing Part of the Civil Court. He cited problems with internet outages and consecutive interpretations that resulted in inadequate translation. “They take more than twice as long, I can’t even clock it.”

Cynthia Cheng-Wun Weaver, a litigation director for the advocacy group, the Human Rights Campaign, who was previously an adviser for the court system’s Office of Language Access, said one reason for these problems is the inadequate training of interpreters.

A full-time interpreter said the last time he got training was at least three years ago. Their supervisor, he said, evaluates interpreters’ performance once a year. The supervisor, however, does not understand Mandarin and can only observe the interpreters’ behavior in court.

Despite all of these problems, the City’s Housing Court has received just three complaints about interpreters between 2022 and 2023, according to records obtained by Documented through a Freedom of Information Law request. Two of the complaints can’t be disclosed because the investigations are still ongoing. The last one is about a Russian-speaking interpreter.

Many Chinese litigants interviewed were unaware that they could file complaints about interpretation. What’s more, because they lack English proficiency, these litigants can’t assess the accuracy of the interpretations. Additionally, the complaint form for court interpretation is available only in English, requiring litigants to seek interpreter assistance to file a complaint against an interpreter.

“Interpreters are the only ones who know exactly what is being expressed by the parties, which means the power they have is hard to imagine,” Nori said.

In a 2015 open letter sent to the chief administrative judge of the New York City courts, then-City Comptroller Scott Stringer cited “widespread language barriers” in housing courts, including the long wait times for interpreters and inadequate multilingual signage and literature. He proposed using demographic data to customize signage and interpretation services for the unique requirements of boroughs. He pointed out that more than 100,000 residents with limited English proficiency in Queens speak Chinese and the Queens courts should therefore have more Chinese-language signage.

TestPost3

“We have to design our entire courthouses — from the security line to the judge’s bench — to help people navigate the process from the moment they step in the door,” he wrote.

Yet, nine years have passed, and little has been done.

“The court’s attitude seems to be, ‘Hey, why don’t you just learn English?’ ” said Nori.