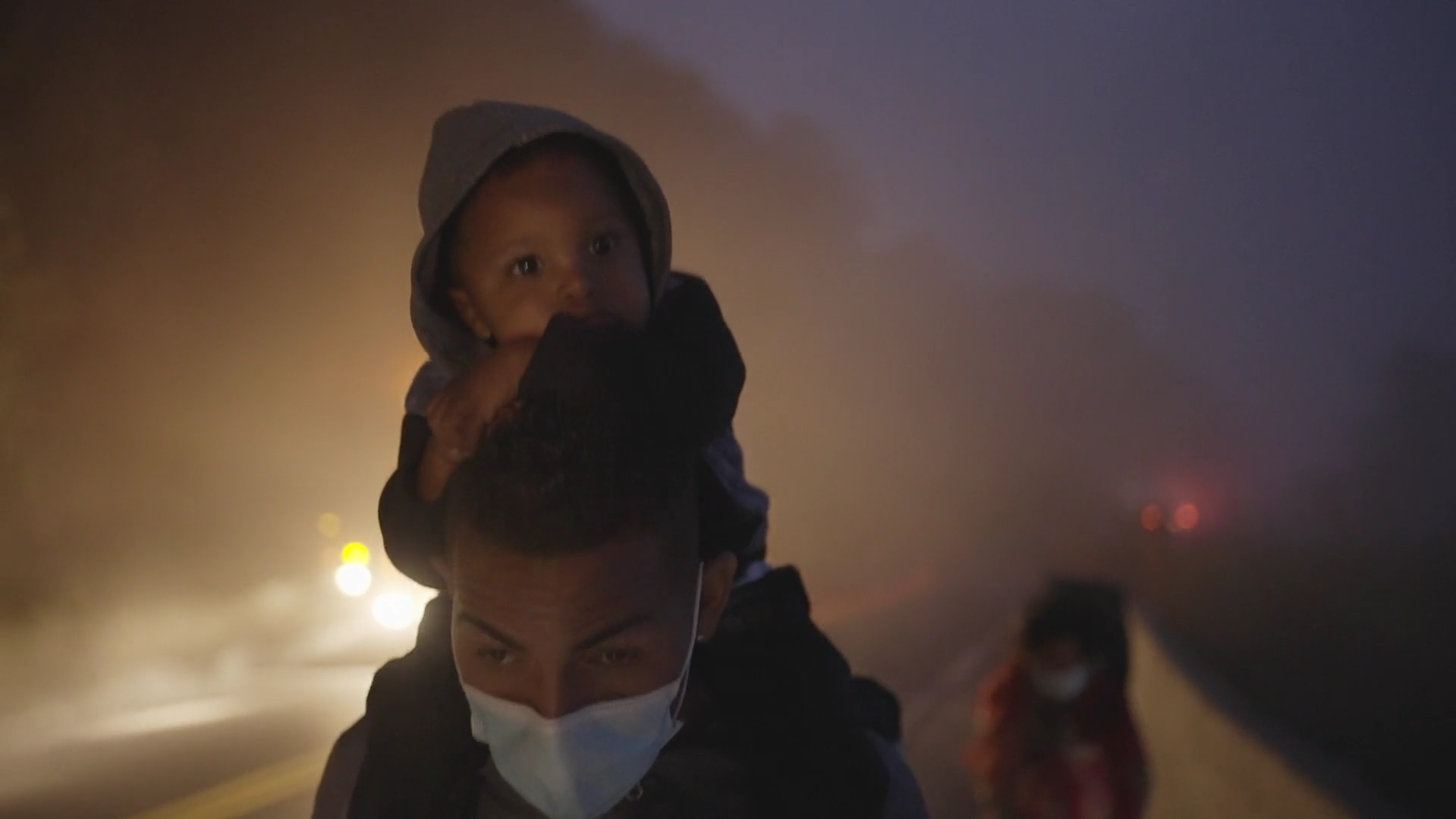

The young boy, no older than 15, looks nervously at the sack of goods before him. The sack is almost as tall as he is and has a makeshift handle strapped on the front. Next to him, two older teens command the boy to pick it up. He tries to lift the sack with his head, holding all the weight of it with his neck under the strap. He struggles, almost drops it. “Have him carry the foam,” someone jokes. The older teens giggle as the boy moves away from the sack. Seconds later, all three are seen each carrying a sack of goods along an abandoned dirt road. Together they are on their way to cross the Colombian border and deliver the goods to Venezuela.

In the documentary “Esto es Frontera/At the Border,” directors Braulio Jatar and Anaïs Michel, follow the lives of two trocheros, people who are familiar with the geography of an area and help others navigate it. In the film, the trocheros also smuggle goods from Colombia to Venezuela. In this scene, the teens carry sacks of foam sheets and plastic products. Other trocheros like them may carry cords and plugs for appliances. Filmed in the city of Cúcuta, the documentary depicts the crisis that has been brewing at the crossroads of the Colombian and Venezuelan border. Since 2014, more than 7.7 million Venezuelans have been compelled to leave their country to seek refuge in neighboring countries and beyond.

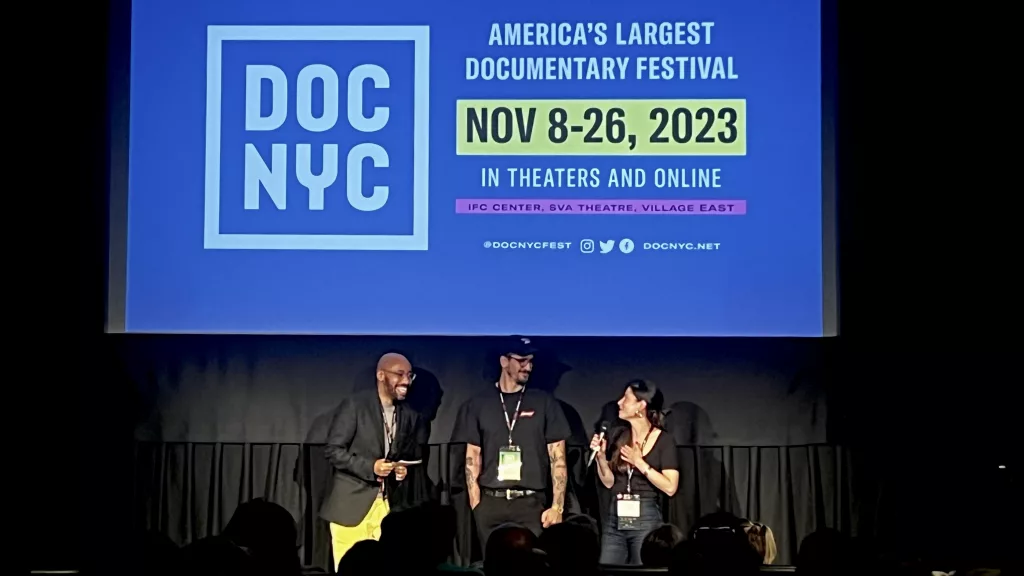

The official selection for this year’s DOC NYC Film Festival, the documentary uses a cinéma vérité approach to vividly capture the everyday life and struggles of Venezuelans looking to survive as they seek to build new communities outside of their homeland. Personal stories and struggles of those affected come to the forefront and provide a humanizing lens to the countless migrants whose lives have been upended by economic hardships and political instability.

“We wanted to put a face to the numbers,” Braulio, who was born and raised in Venezuela, told Documented’s Rommel H. Ojeda at the worldwide premiere of the documentary on Saturday at Village East by Angelika. The director spoke with Ojeda about the process of making the film and the challenges they faced.

Rommel Ojeda: You said the film came to be after you and Anaïs took a trip to the Colombian and Venezuelan border. What was something that stood out to you?

Braulio Jatar: The most surprising thing we saw was the number of people crossing through these illegal pathways, called trochas, from Venezuela into Colombia and vice versa. People were going to Colombia to buy goods, and then went back to Venezuela. A lot of people were going to Colombia just to eat at the soup kitchens, … which were serving around 3,000 to 5,000 daily. The whole area was filled with people just trying to survive.

How long did it take for the documentary to be made?

We started in May of 2019 and it’s premiering now in 2023. November, so a little over four years.

Did you shoot during the COVID-19 pandemic too?

The pandemic sidetracked us aggressively. It was a very difficult obstacle to overcome in the making of this film. But yeah, we somehow managed to do it… [the pandemic] is a part of the story, even though it’s not mentioned. You will see pandemic imagery that we’re all used to at this point.

The film follows the perspective of coyotes [smugglers]. Could you talk a little bit about how the decision to focus on them came to be?

We chose the name coyotes because it is the name most people recognize. But they are also known as trocheros. Their main job is to transport merchandise from Colombia to Venezuela, and then they help people from Venezuela traverse the paths to Colombia because not everyone knows what the right way is. So they are kind of guides. We chose their perspective because of the nature of the work and how the work itself shows the crisis of just trying to meet the basic necessities in Venezuela.

You are also from Venezuela. I assume this story is personal for you.

That first visit was very shocking, and till this day it’s hard to see some of the things that we witnessed there. It’s just very catastrophic. That border area is a dangerous place. It’s a place where, also, people are taking advantage of [others] a lot. There is a lot of need — everybody is looking for really basic basic things to survive. It’s very heartbreaking. Especially because they are people that you have shared something with back home. There are a lot of people from Venezuela that have to make difficult decisions.

New York City has received thousands of Venezuelans since the Spring of 2022. But the film touches on the numbers, and it shows that the United States is not their main destination.

Most of the ones that are making their way to the United States are Venezuelans who have already attempted to make a life elsewhere in the Americas. It’s people who have tried in Ecuador, in Colombia and have not found a community. They are also used to making these types of journeys and leaving it all behind so that doing it a second or third time is no longer difficult for them.

For those interested in watching the film. What is something that you would like them to keep in mind?

TestPost3

We hear all the numbers, and the numbers are pretty crazy. There are those tens of thousands of [migrants] that have arrived in New York City. There are millions of them in Colombia and more elsewhere. So, our goal with this film was to provide a face for those numbers and provide an actual story. Something [the viewer] could connect to and, hopefully, empathize with.

I feel like people are interested in understanding a tiny bit more about these people and why they’re doing what they’re doing.

The documentary can be watched online at the DOC NYC’s website until November 26.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.