Brian Aguilar Avila, a 27-year-old Neural Engineering Laboratory Administrator at City College from Argentina, feels a familiar uncertainty knowing that the fate of the program Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals could be decided at the courts next month.

He had been in this situation five years ago, when, as he left his doctor’s office on the sunny afternoon of September 5th, 2017, his phone vibrated with a notification flashing across the screen: Attorney General Jeff Sessions rescinded DACA. The program had given him the opportunity to work legally, obtain a social security number, and travel abroad using Advance Parole (AP) — his ability to work legally in the US was in jeopardy. And it could happen again.

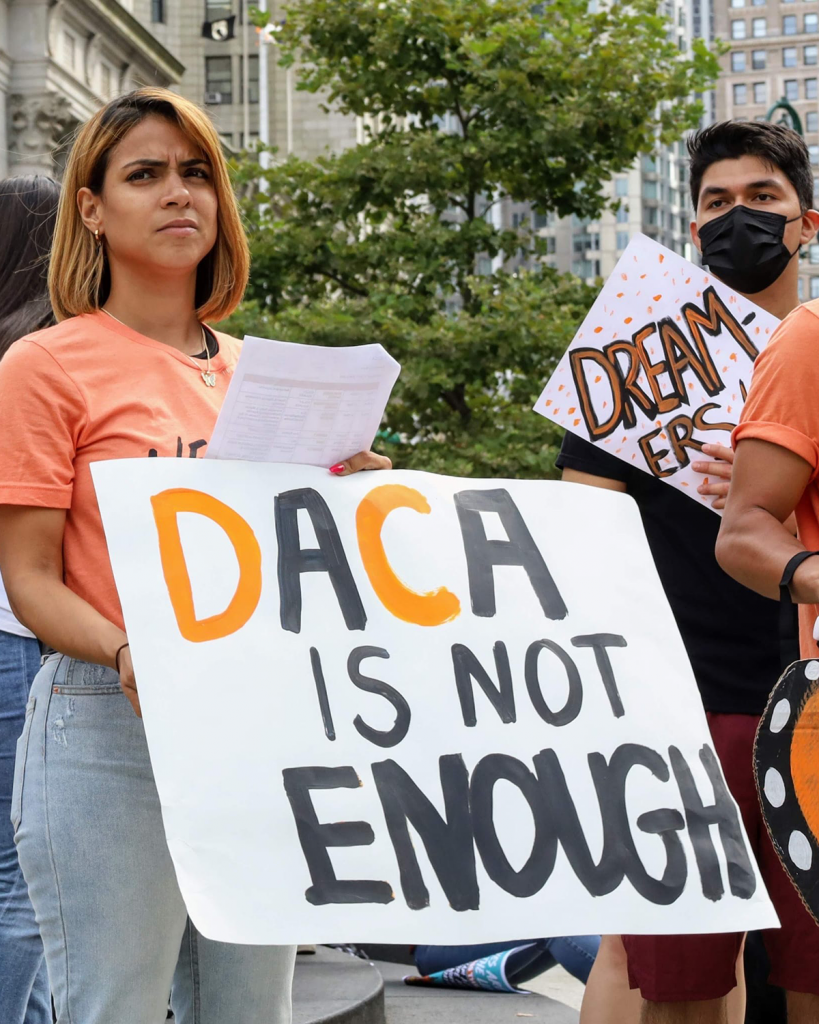

Documented heard from over 100 Dreamers, who, like Aguilar Avila, are living in a state of anxiety and uncertainty due to the program’s volatility. 93.26% of 89 active-DACA-recipients said that their mental health had been impacted by the program, with 33% reporting that they had taken therapy sessions. Aside from impeding Dreamers’ from planning their careers, lives and relationships past the two year expiration times, the program’s limitation has also affected the wellbeing of their family members.

“It’s as if we are hanging by a thread,” Aguilar Avila said.

The program was announced by the Obama administration on June 15th, 2012, and implemented through an executive action a month later, with the goal to provide protection from deportation to children who were brought to the U.S. and lived here without documentation. Since the program’s announcement a decade ago, more than 690,000 beneficiaries have applied.

Aguilar Avila, who lives in Yonkers, has been a beneficiary of the program since 2012. After he graduated as the valedictorian of his class in 2013, he applied to CUNY, SUNY, and private schools around the country. Because, at that time, DACA students were still considered as international students, he could not consider private colleges due to tuition costs for international students. The process made him feel beat down by the immigration system. Regardless, he obtained his B.E. in Biomedical Engineering from City College in 2017, graduated with a MSEd in Higher Education Administration in 2021, and is now pursuing a PhD in Urban Education from the CUNY Graduate Center.

Regardless of these accomplishments, “I am an American,” Aguilar Avila says. “Sure my heritage is from Argentina, but I know nothing of Argentina. I know everything about the U.S. I learned history in the U.S. It doesn’t make sense that I will not have a green card by the time I am 30. I don’t fit in here because the U.S. is not accepting me. So where do I belong? I am de-facto stateless,” he added.

“Having to renew DACA is always at the back of my mind… but I don’t know what is going to happen in the next few months,” he said.

Also read: How DACA Changed in 2021

In April of 2017, a study published in The Lancet Public Health that surveyed 14,973 respondents, of whom 3972 were eligible for DACA, found that the rates of moderate or severe psychological distresses in the DACA eligible group had dropped by 40% after the program had passed. However, after the program was terminated, another study showed that stress levels among DACA recipients had increased, and that “40.7% met the clinical cutoff for distress from the PTE indicative of posttraumatic stress disorder,” resulting from the uncertainty of the future of DACA.

The drawbacks of the program not only affects the individual’s mental health, but also the wellbeing of the family, says Eva Santos Veloz, 32, an organizer with United We Dream, who is also a Dreamer.

Since her arrival to the States at the age of 3 from the Dominican Republic, Santos Veloz grew up in the Bronx and was able to apply for the program in 2014. At that time, she was living with her children in a shelter and DACA became her way out of homelessness.

However, she says, the two year time frame of the program has made her lose three jobs because of renewal processing delays.

“The bank would send you an email 180 days prior to the expiration date of your EAD, and then again in 100 days, and then in 50 days — that is a lot of pressure for a person’s mental health. Imagine going to work and basically seeing a time clock on your future,” Santos Veloz explained. USCIS had taken 8 months to process her renewal which on average takes five months. She lost her position as a relationship banker at the institution.

As Santos Veloz waited for her permit to arrive, the economic impact externalized at home. “It was really sad for me and my kids — because there is nothing you can do about it,” she added, regarding losing her employment. “It’s as if you have to prove every two years why you deserve to be here.”

When the grandfather of her children, ages 5,11,13, passed away suddenly during a trip to the Dominican Republic, Santos Veloz said her children wanted to go see him. Because of her status, she was not able to travel without advance parole — which had to be applied for in advance. “That affected them very much. Because they weren’t able to understand why. And they weren’t able to say their goodbyes… and I know so many children are affected day to day by the same experiences. It’s just not my story. My story is one of a million stories,” she said.

Also read: NYC Immigrants Hold Out Hope for Build Back Better’s Path to Citizenship

Santos Veloz added that her family, who have green cards or are citizens, have avoided visiting their family in the Dominican Republic multiple times because they don’t want to travel without her. “It makes me feel guilty,” she said, adding that the family has had to adjust as if they also had DACA.

Cannot re-enter the country without Advance Parole

Under the program, DACA recipients can only travel for humanitarian, educational or work related reasons with advance parole. Aguilar Avila had to apply for the travel document back in January, when his grandmother, who he had not seen for more than two decades, passed away.

“I had some nostalgia of the things I remembered… and I was emotional but I was also sad, very sad, because I did not want to go there under those circumstances. My grandma had wanted to see me when she was in the hospital bed… And it hurt” he said, recalling his grandmother had cried on the phone when she spoke with him a few days before she passed..

“And it hurt more that I had to go [Federal Plaza],” at the Bureau of Citizenship and Immigration Services building where he had to apply for advance parole. The agents made him feel like a “prisoner.”. “Like come on dude, I am paying to go to Argentina to pay my respects,” he added, explaining his AP had been denied at first when the personnel there mistakenly said he didn’t qualify because he did not bring his original passport– further delaying his departure.

Jessica Smith Bobadilla, a U.S. based immigration and human rights attorney who has been practicing for two decades, says that the advance parole process can be very cumbersome. She represented Luis Miguel Grijalva Morales, a Dreamer from Guatemala who ran in the Tokyo Olympics last year, and recalls that they had a very short time frame to apply for the traveling permit due to how the qualification works. She remembers being “glued” to her phone to ensure that she would not miss the calls from the USCIS agents processing the application.

“During that time we had to go through lengths that would be impossible for DACA recipients who are not represented, or, even if they were represented, may not have the same outcome,” she says, explaining that Grijalva Morales had to, after being approved, run to a COVID testing facility to get the results so that he could depart a few days later.

“One of the things that I recommended was that the administration consider if DACA holders, during renewal process, could justify reasons for travel under the scheme [of advance parole], that a travel option be available with certain conditions attached to it…. And also that the applicant would still have to meet the criteria if asked by a CBP officer… as to what the nature of their trip has been,” Smith Bobadilla said.

TestPost3

Allan Wernick, Director and Attorney-in-Charge at CUNY Citizenship Now, an initiative which has helped more than 2000 dreamers with applications and renewals in New York, told Documented that “the program could have been structured so that Advance Parole was automatic rather than discretionary,” and that “it could be done by administrative guidance.” Wernick also cited that a program like advance parole is routine in a program like TPS, but not in DACA.

Regarding the court hearing taking place on July 6th, Wernick says that the only way for DACA to be protected would be through legislation.

“I am still upset that [DACA] hangs on a thread. They always say they have a plan, that congress has a plan, and that Trump had a plan, but it always dies. There’s no one who cares…I want people to know that I am in this situation and I am stuck,” Aguilar Avila said.

Also read: DACA Renewal Checklist