This piece was reported and published in a partnership between Documented and THE CITY.

With only days left in the legislative session, Albany lawmakers are pushing to put regulations for a largely unregulated immigration bail bond industry, notorious for literally shackling clients with crippling debt and bulky ankle monitors.

Unable to afford bail for their release from federal detention centers in the tri-state area, many undocumented immigrants turn to for-profit bond companies for help.

The companies post bail on the individual’s behalf — the median amount is $7,500 for cases in New York City and State — so they can be free as they await court dates.

But the contracts are egregiously lopsided, state lawmakers and immigrant advocates assert, with the bond companies charging exorbitant fees and making clients wear invasive ankle monitors. Immigrants report paying as much $450 a month for the devices — for years.

“Emotionally, it destroyed my life,” said one 25-year-old Salvadoran man who was previously trying to seek asylum in New Jersey, reflecting on his time in detention and the abuse he says he faced from an immigration bond company.

The man, who preferred to remain anonymous, said he paid Libre by Nexus $420 a month for an ankle monitor over about three years while he was waiting for his case to proceed in the immigration court backlog. The process often takes years to complete.

Assemblymember Harvey Epstein, who represents parts of Manhattan, and State Sen. Jamaal Bailey, who represents parts of The Bronx, said the immigration bond industry is overdue for oversight, so they want to establish a regulatory framework.

“When I heard about the abusive system that we see that immigrants face when going to bail bonds people, I knew we had to do something about it,” Epstein said.

The legislation they are sponsoring, called the Stop Immigration Bond Abuse Act, would put a sliding cap on the amount that bond companies could charge for their services, as well as prohibit the use of electronic monitoring devices and establish a new licensing system to provide bail and other services for detained immigrants. Violators could be charged with a misdemeanor and subject to litigation, according to the bill.

“We don’t see the oversight in other states as we’re trying to do here in New York, and I think this could be a model for the nation,” Epstein told THE CITY and Documented.

Threats and Misrepresentations

Epstein noted that there are also good organizations providing immigration bail services, highlighting groups like Envision Freedom Fund, a Brooklyn-based nonprofit. Envision, which advocates for the regulation of for-profit bond firms, uses charitable contributions to provide bonds for detained immigrants and doesn’t charge fees or ask to be paid back.

But the lawmakers and immigrant advocates pointed to Libre by Nexus, a Virginia-based bond company, as an example of a bad actor in the sector.

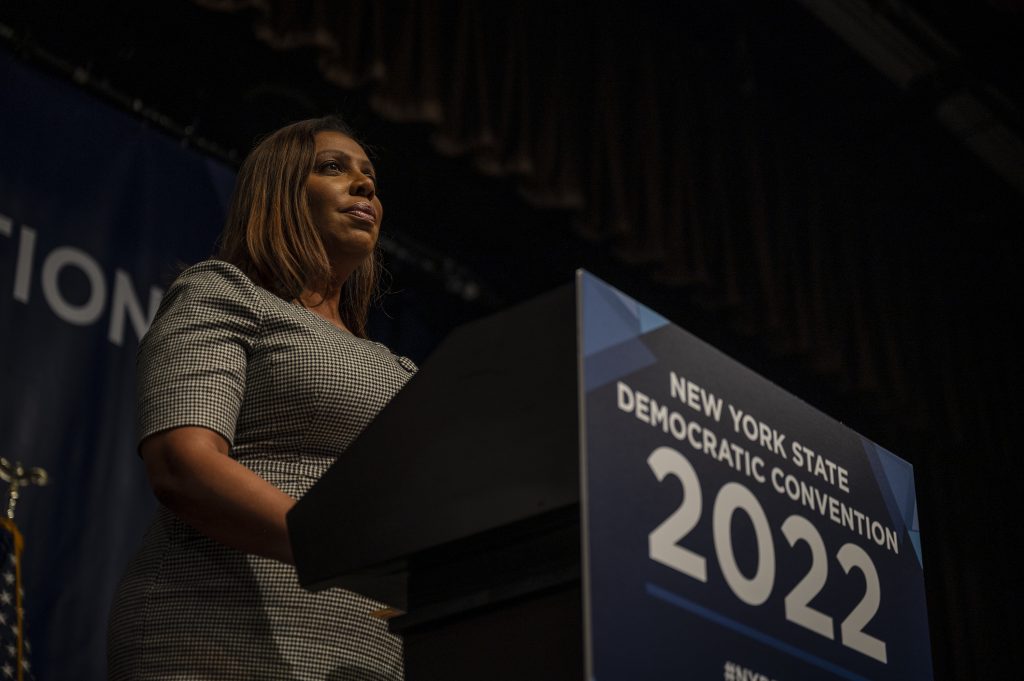

In 2021, New York Attorney General Letitia James, along with the attorneys general of Massachusetts and Virginia and the U.S. Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, sued Libre in federal court, alleging that the company preyed on immigrants in detention.

The plaintiffs alleged that Libre deceived clients into signing misleading contracts not in their native language, mischaracterizing the services provided. Additionally, the AGs alleged Libre led customers to believe that their fees would be refunded once they paid their debt off, but in reality, no fees were returned.

In New York, Libre told clients that they would receive free legal representation, but the company only gave referrals, the suit alleges.

Libre also threatened its New York clients with re-arrest, detention and deportation if they failed to make monthly payments or removed the ankle monitor, according to James’ section of the complaint court documents.

That case is ongoing. In a legal filing, Libre by Nexus denied threatening or deceiving clients.

Libre by Nexus CEO Mike Donovan defended his company in a statement to THE CITY and Documented — and said he supported the pending legislation in Albany.

“I’m sad that many people seem to misunderstand our business,” he wrote. “I will extend an invitation to any legislator or advocacy group to meet with our team or visit our facilities.”

Despite being castigated by lawmakers who introduced the bills, Donovan said his company “will work to advance its passage.”

He added: “Libre hasn’t used GPS tracking bracelets for years, and it isn’t a practice we intend to revisit in the future.”

‘Jesus, I Can’t Do This Anymore’

The young man from El Salvador was one of Libre’s many clients nationwide.

He first entered the United States on his own in 2015, fleeing gang persecution back home, he said. But almost immediately upon arrival in the United States, he was swept up into the immigration detention system, spending more than a year at centers in New Jersey while he unsuccessfully tried to get asylum.

“I cried night and day, laying in my bed,” he said in Spanish.

At one point, an immigration judge set his bond at $20,000, he said.

“That was really hard for me — the hardest thing I’ve experienced in life,” he said.

He eventually heard about Libre — meaning “free” in Spanish — through a local New Jersey and New York-based organization that supported him to find legal help and other aid during his time in detention.

“I couldn’t find any way out, so I had to accept it,” he said of the bail bond contract.

He said he had to give Libre a downpayment between $5,000 to $7,000 to get released, for which he had help fundraising through a local advocacy group, and then pay $420 a month for an ankle monitor that would be attached to his foot for about three years. He was also required to pay back the rest of his bail over time.

“I wasn’t able to see the contract because I didn’t have the option to actually view it [in the detention center] — only over the phone. Obviously with my anxiety I just told my friend, ‘OK, sign the contract.’”

He was released in 2017 — but the elation at being out of the facility was short lived. The man, who lives in the Jersey City area now, said he was constantly bombarded with calls from Libre — sometimes at 2 or 3 in the morning — telling him that he was late on payments, and that he had to charge his ankle monitor.

“They harass you,” he said. “I couldn’t even sleep peacefully.”

To charge the ankle monitor, he would sometimes have to stand next to the wall for about an hour so that it could connect to an electrical outlet. He stopped wearing shorts out of embarrassment. He had trouble finding work because of how the ankle monitor looked, he said.

The monitor also scarred and bruised his ankle and foot, he said.

“I was suffering,” the man said. “I was saying, ‘Jesus, I can’t do this anymore.’”

He felt the immense financial burden, too. The man was only able to pay back about an additional $1,000 on top of the down payment he gave with the contract, he said — and continued paying $420 a month for the ankle bracelet. He struggled to make ends meet, constantly worried about whether or not he would make rent or have enough food.

“I would think — I’m going to be left without anything to eat. Where am I going to live?” he said. “It was so, so difficult.”

Libre employees told the man that his bills would be sent to collections, but he is unclear if that ever happened or where his status with Libre stands now. He stopped paying for the bond years ago, and hasn’t paid for his ankle bracelet since he cut it off himself in 2020 when an attorney told him it wasn’t necessary to wear one.

The man is so much happier today without any ties to Libre or the ankle monitor, he said. “It’s such a relief,” the man said. “After I cut it off, I felt like a new person.”

‘Profiteering of Human Suffering’

Carl Hamad-Lipscombe, executive director of Envision Freedom Fund, said he’s been advocating for baseline regulations for the industry for years, speaking with lawmakers about the need. But he said many didn’t realize that there was a problem.

“Many of them assume that these companies were already regulated,” he said. “Then when they find out that they’re [largely] unregulated … most of them are super supportive.”

A diverse coalition of organizations, led by Envision Freedom Fund and African Communities Together, a nonprofit that works for the civil and human rights in New York and elsewhere, has been organizing a campaign called Break the Shackles. Their goal is to end profiteering by immigration bond companies with the passage of the Stop Immigration Bond Abuse Act.

“The person accepting the contract doesn’t fully understand all the details of the contract,” said Robert Agyemang, New York director of the nonprofit African Communities Together.

His organization works mainly with immigrants from western African nations, including Ghana and Nigeria, caught in a bind with these bond companies. Agyemang said most of them have contracts with Libre.

And recently, he said, many have had their ankle monitors swapped out for cell phone tracking apps — another form of invasive surveillance.

Albert Fox Cahn, director of the Surveillance Technology Oversight Project, a nonprofit advocacy group focused on law enforcement monitoring tools, said the use of smartphone tracking apps has been growing in the public and private sector for years, as both see them as more cost effective ways of surveilling people.

TestPost3

“The smartphone stuff, while it’s marketed as somehow being cutting edge, remains just as traumatizing for the people who are forced to use it,” said Fox Cahn.

Fox Cahn said it’s about time this immigration bond industry gets regulated.

“These private bond providers, they’re profiteering off human suffering,” he said. “And it’s really the Wild West out there for how this technology is used.”

The Senate majority leader and Assembly speaker’s offices did not return calls for comment.