The New York State Division of Criminal Justice Services (DCJS) forwards information on certain immigrants to Immigration and Customs Enforcement so that they can be apprehended, Documented has found.

It’s a practice the agency has long denied; spokesman Justin Mason said last year that “[a]ny assertion that DCJS is somehow willfully feeding information to ICE in order to assist with deportations is simply false. DCJS does not proactively work with the federal government to provide information.”

In 2005, DCJS “and ICE developed a mechanism to flag the arrest record of offenders whose New York State criminal history includes a record of having been deported. When the state agency receives fingerprints belonging to one of these previously deported individuals, DCJS forwards an electronic notice to ICE’s Law Enforcement Support Center (LESC) and a real-time Blackberry notification to ICE’s New York City fugitive apprehension unit,” according to DCJS’ 2009 annual report from the state agency.

The report also said that DCJS’ Office of Justice Research and Performance has “coordinated interagency efforts to increase the number of deported criminal alien records on the State Computerized Criminal History (CCH),” and has developed a partnership with ICE to conduct “periodic data matches to update New York State criminal history records with deportation data from ICE.” The effort allowed DCJS to add 16% more names of deported immigrants with criminal histories into its CCH database in 2009, the report said.

Janine Kava, the DCJS director of public information, confirmed that it remains DCJS policy to automatically forward a notification to ICE when a fingerprint taken by state authorities brings up a record that includes notice of a previous deportation.

She explained that the coordination takes place because “reentering the country after being deported is a federal crime… We make ICE aware that someone who has been previously deported and has an NYS criminal record has reentered the country.”

While illegal reentry is a federal crime, previously deported people who are rearrested in the interior of the United States have likely not yet been convicted of it. The notification to ICE might be the federal government’s first indication that they are back in the country.

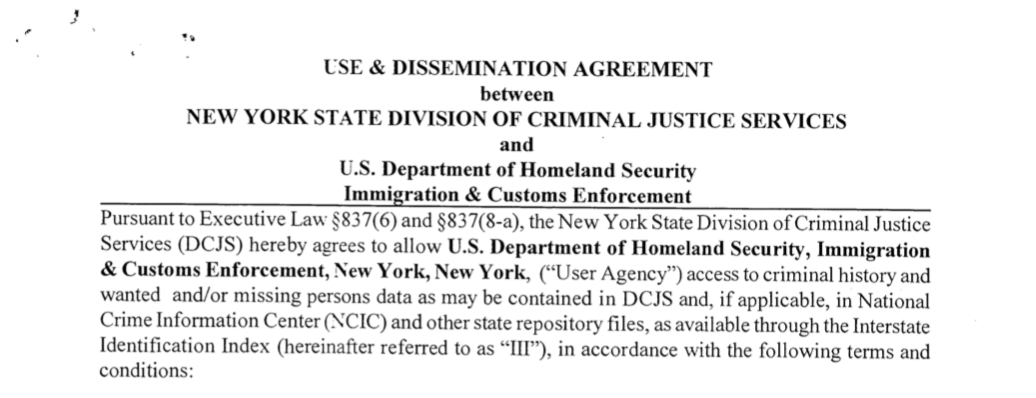

Through public records requests, Documented also obtained active data-sharing arrangements, known as Use & Dissemination Agreements, between DCJS and four New York ICE offices — in Rouses Point, Batavia, Latham, and New York City — as well as the ICE Northeast Field Intelligence Unit. DCJS additionally signed an agreement with the Customs and Border Protection (CBP) office in Grand Island, New York. All of these agreements were signed between 2006 and 2011.

Documented also obtained agreements with Homeland Security agencies and sub-agencies that are less actively involved in immigration enforcement, such as the Transportation Security Administration and U.S. Customs Office, for a total of ten data-sharing agreements.

The agreements allow authorized agencies to pull up detailed rap sheets on suspects using fingerprints and biographic data. Though they stipulate that DCJS databases can only be used for the purposes of a “criminal investigation” only, federal illegal entry and re-entry are technically federal crimes, meaning ICE immigration investigations could qualify.

According Kava, all these agreements remain active. She defended the practice as in keeping with the law enforcement mandate.

New York state has a relatively robust sanctuary framework: only a single sheriff participates in the controversial 287(g) federal program, which deputizes local law enforcement officers — typically corrections personnel — to detain immigrants for questioning and arrests. The state’s top appellate court ruled that local law enforcement cannot honor ICE detainer requests to hold immigrants in custody for longer than their normal release times; and Governor Andrew Cuomo has issued an executive order and further amendment restricting state agencies’ cooperation with ICE. New York prohibits civil detentions in most state facilities.

This doesn’t mean that ICE gets nothing from New York law enforcement agencies, or that every denial of cooperation between state personnel and ICE is genuine. In January, for example, Documented revealed that, despite repeated assurances that no court personnel were communicating with ICE about enforcement actions in state courthouses, some local officers had been in touch with ICE agents about arrest targets showing up in court.

Though ICE already has access to criminal histories through federal databases, such as the FBI’s National Crime Information Center (NCIC) and National Data Exchange (N-DEx), having direct access to local databases allows it to get more granular information on potential targets. Ryan Muennich, a staff attorney at the Immigrant Defense Project, said that among the useful information that ICE could obtain from the state are up-to-date mugshots that could help identify targets; current addresses that would enable home raids; and more detailed information on state-level criminal charges and convictions that could allow ICE to assert removability.

These types of data-sharing agreements aren’t rare, and, according to NPR, this data access has already been used operationally by ICE across the country for years. However, even in its own materials, ICE hasn’t directly referenced data exchanges with New York’s DCJS.

One of the conditions of access to the databases is that the user agency must run a program that compiles a log of all the criminal history queries that the agency has made, and allow an internal “criminal justice coordinator” within the user agency itself to “review this log and validate that all usage was for official purposes.” These logs are then subject to periodic audits by DCJS, which is supposed to ensure that only certified personnel have made searches, and only for legitimate purposes.

In total, five out of the ten agencies in the agreements Documented obtained had been audited since 2013, because only those five had performed criminal justice searches in that timeframe. These audits did not find unauthorized access according to DCJS’ standards. Kava did not say which five.

When someone is taken into immigration custody, neither they nor their attorneys are typically told what data was used by immigration enforcement authorities to find them, or what brought them to ICE or CBP’s attention. However, some immigration attorneys have said that detailed DCJS rap sheets, which look different than the ones coming from the FBI, have been used by ICE prosecutors in immigration court.

Muennich, the IDP attorney, pointed out a complaint filed in the federal court for Eastern District of New York last year by an ICE deportation officer named Kenneth Lopez against a Salvadoran man named Rommel Jossael Quintanilla-Moreira. As part of his sworn statements, Lopez writes that “[o]n November 23, 2016, ICE was notified by the New York State Division of Criminal Justice Services… that the defendant had submitted fingerprints in connection with a civil inquiry for ‘Adoption/Guardianship/Custody F/P.’ In connection with that inquiry, the defendant provided the following address,” with the address included.

The account contradicts Kava’s assertions that the notification to ICE only goes out when an immigrant is arrested in New York. In this case, it appears that DCJS flagged Quintanilla-Moreira based on some sort of custody application and provided the notification of his updated address to immigration agents.

TestPost3

“This is an ICE problem, but it’s also a New York state problem, a problem that arguably should have been resolved by the governor’s executive order,” said Lee Wang, a senior staff attorney at IDP who has been tracking the ways in which the state and ICE communicate and who first identified the immigration-related passages in the old DCJS reports.

A spokesman for Gov. Cuomo deferred to DCJS’ judgment as to whether the policy violated the governor’s executive order, which generally bars state agencies and employees from sharing data with immigration enforcement authorities unless required to by law. DCJS maintained that its policies did not go against the governor’s orders. “The Division of Criminal Justice Service has absolutely no role in assisting the federal government with civil immigration matters and to suggest that we do is not only wrong but irresponsibly stokes fear among individuals that the State is committed to protecting,” Kava said in a statement.

After reviewing materials provided by Documented, State Sen. Luis Sepúlveda (D-Bronx) said “the agreement was there, the question is how enthusiastically it has been put in effect. Now, with the Trump administration, I’m sure it’s a daily occurrence.” As far as the appropriateness of the data-sharing, he said he is “one hundred percent against it.” As a result of the revelation from Documented, Sepúlveda said that he would be looking into what other areas the state and ICE might be exchanging data.

He added that he and other members of the legislature exploring investigating what agencies might be sharing information with ICE. “Where federal law doesn’t prevent us, preempt us, from taking direct action, I’m going to explore what action we can take legislatively,” he said. “We here in New York are not going to stand for that kind of stuff.”